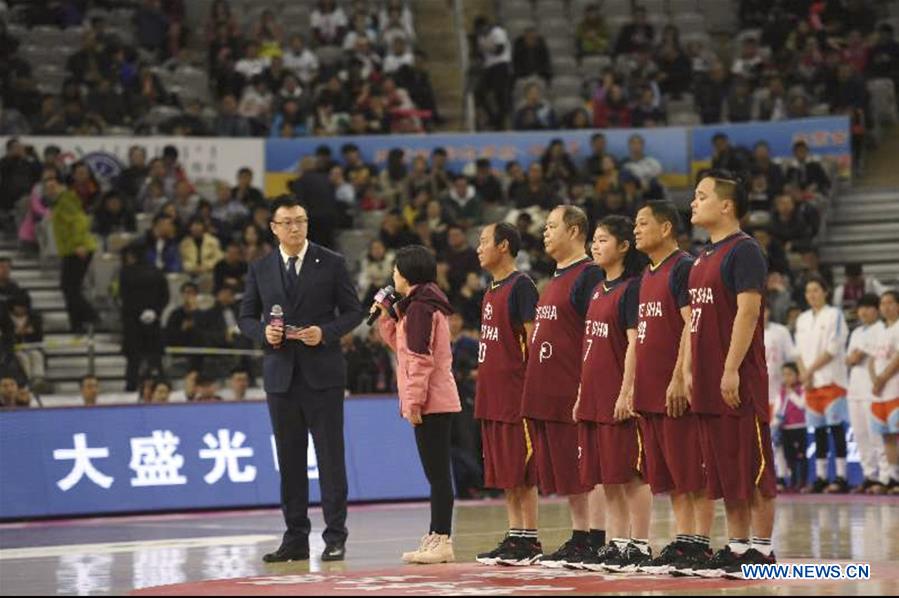

The Yesha team is introduced to spectators during the WCBA All-Star Game in Hohhot, north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Jan. 27, 2019. (Xinhua/Peng Yuan)

By Sportswriters Ma Xiangfei, Shuai Cai, Yuan Ruting and Lin Deren

BEIJING, May 12 (Xinhua) -- A thump. Another thump. And another one. The sounds reverberated through an empty stadium in Inner Mongolia. Sunlight poured in through the windows, illuminating the court and the surrounding green walls.

Liu Fu clumsily bounced a basketball, held it up, tried to shoot for the hoop and missed.

Liu didn't know how to play basketball. His thick, rough hands were more used to holding a drill than a ball. However, the former migrant worker would stand in front of hundreds of thousands of people and display his awkward basketball skills in the Chinese women's league All-Star Game on January 27, 2019, in memory of a basketball-loving boy whom he had never met but who now was already a part of his life, literally.

Liu's memory often flashed back to the night of April 27, 2017, when he lay in the surgery room of the Second Xiangya Hospital in Hunan Province waiting for an organ transplant. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw someone come into the room, carrying a box.

"They are of excellent quality," were the last words Liu heard before he lost consciousness, according to a story released by the Beijing News.

In the box were the lungs of a 16-year-old boy, Yesha, who had died early that morning.

In retrospect, April 27 was an ordinary day for most people in the world, yet on this very day a lot of people saw their fates forever changed - among them, a lively boy whose life stopped at 16, two devastated parents and seven patients, some of whom were terminally ill.

YESHA

Just a day before, Yesha was a happy high school freshman whose favorite pastime was playing basketball.

One widely circulated picture online recorded the precious moment when Yesha, in a black sweater and dark blue school uniform pants, was playing basketball with his schoolmates in the schoolyard. He was inside the arc, facing the boy who had just successfully grabbed a rebound. Yesha was observing the boy's movements, his right foot stepping up and it seemed he was about to act the next second.

Yesha seemed to have everything. Besides being athletic, he was also an academic star at his high school in Changsha, winning the top award at his school's mathematics competition and was considered a model student. Standing 180cm tall, he had the best features of both his parents; slightly curly hair and thick eyebrows from his father, and lips from his mother. He could well have fit the role of Prince Charming in a school play.

"Both my wife and I are plain-looking people and it was strange that my son was so handsome, several times more handsome than me," Yesha's father Papa Ye said, a smile breaking out on his face.

No one can imagine that death would soon seize the industrious and high-spirited student. Two years on, Papa Ye can still clearly remember the painful scene that unfolded on April 26, 2017.

On that day, Yesha called his father from school, saying that he had a terrible headache.

In an interview with the Beijing News, Papa Ye recalled his last conversation with his son at noon that day.

"I told him to go home first. I should have let him go to the teacher for help! If only he went to the hospital instead of coming back home, none of this would have happened," he said.

Papa Ye hurried home. When he opened the door, he found his son lying unconscious on the floor.

"I called his name over and over again, but there was no reply," he said ruefully, his face hidden behind cigarette smoke.

Papa Ye rushed Yesha to the Brain Hospital of Hunan Province, a 10-minute drive from his home, but it was too late.

Doctors exhausted all possible means of emergency treatment on Yesha and the diagnosis was dire -- severe intracranial hemorrhage, weak breath, deep coma and no reaction to outside stimulation. Yesha's parents were told to prepare for the worst.

"I didn't want to think of the worst case scenario but to tell you the truth, there was a little voice in my mind that told me 'it could happen'," Papa Ye said, clearing his throat.

Yet the worst moment came at 7:20 the following morning. Yesha was pronounced brain-dead less than three weeks before his 16th birthday.

At around the same time, organ donation coordinator Meng Fengyu received a call from the Brain Hospital telling her there may be a potential organ donor.

Meng, then 26, raced to the ICU ward and saw doctors speaking to Yesha's parents.

"They were listening to the doctors attentively and asking the occasional question," Meng recalled.

Doctors explained Yesha's irreversible situation and mentioned the possibility of organ donation, considering that Yesha was young and healthy and his organs were in perfect condition. Naturally, the recommendation was met with a resolute and desperate "No" from Yesha's mother.

Hearing this, Meng backed away. She did not even walk into the room because she understood how heartbroken the parents were at that time - Yesha was their only child, and he was such a brilliant boy.

"I think the most painful thing in the world is losing your child. I didn't have the heart to persuade them, as Mama Ye was already strongly against the proposal," said Meng.

Meng left the ICU ward. While she was walking out of the door, Papa Ye was desperately questioning his friend, also a doctor, for other solutions.

"Isn't there any other way? Really? No other way?" Papa Ye asked his friend in despair.

"No, it's too late," his friend said.

Meng understood their previous refusal. In a country with several thousand years of history, the idea of cremating a family member's body which is not "complete" is still not acceptable for many Chinese, especially older generations.

As the ancient philosopher Confucius put it over 2,500 years ago, people's bodies - including every hair and piece of skin - come from their parents, and they must not be injured or wounded. This was considered the beginning of filial piety, a central value in traditional Chinese culture.

Consequently, when China started a voluntary organ donation trial in 2010, only just over 1,000 people registered.

However, Meng was very surprised to find that less than half an hour after she had left the hospital, another call came in, this time from the Hunan Red Cross telling her the parents of a 16-year-old brain-dead boy wanted to learn more about organ donation.

"I was astonished," Meng said. "Wasn't this call about Yesha's parents? What happened in the past half an hour that made them totally change their minds?"

Fast-forward two years, and when asked about the reason for their change of heart, Papa Ye said that in that half hour, he absorbed the fact that his son would never return, and he was determined to realize his dream for him.

"His dream was to become a doctor, to save lives," he said.

Papa Ye and Mama Ye eventually met with Meng and signed the organ donation paper.

"He ticked in the checkbox in order - the corneas, the heart, the liver, the kidneys. He was fast and determined," Meng recalled.

Once he had almost finished filling out the form, Papa Ye checked himself at the choice of "Lungs".

"Shouldn't we leave at least one organ to our child?" he said to himself.

However, his hesitation was soon erased when doctors told him a terminal pneumoconiosis patient would rely on his decision for the chance of life.

"I wanted to leave an organ to my son. But his lungs can save a life, so I decided to donate them as well," Papa Ye said.

"Looking back, I believe I did the right thing," he continued, clearing his throat again. "At least he left something behind in the world. Our hearts are not completely empty.

"The biggest regret is that we did not donate more. I later learned that his organs could have saved up to 11 people," Papa Ye said.

"Un...unlike people who die in car crashes," he suddenly stuttered, "His, his organs were in great condition."

"Just so you know, my boy's lungs were the best! One day he came back from school and said to me, 'Daddy, Daddy, do you know that I won first prize at school today?'"

"'In what competition?' I asked."

"'My vital capacity is the largest in my grade!' he said. His vital capacity was the best among 400 students in his grade," Papa Ye said, his face lighting up with rare laughter.

LIU FU

Now Yesha's perfect lungs were in Liu Fu's body.

When Liu regained consciousness the next day, he immediately knew that the surgery was successful. In almost 20 years, he had never breathed so comfortably.

"I still wore an oxygen mask but I knew it was successful, because I could breathe on my own. The suffocating feeling disappeared and I could breathe smoothly," he said.

Before the surgery, Liu was very calm. If the transplant surgery worked, it would be a rebirth for the then-47-year-old. If it didn't, Liu saw it as an eventual relief. But there was a lingering hope in his heart that he could be cured.

For 20 years, Liu could not work, and in the last couple of years before his surgery, he could barely breathe; his rotten lungs tortured him so much that he felt like the living dead.

In the early years of his life, Liu, from Lianyuan county in central Hunan, struggled to support his family as he became one of China's millions of migrant workers, traveling between different construction sites, factories and mines looking for work. For Liu, he was skilled at drilling holes in rocks down mineshafts, and became used to hearing the "boom" of explosives while watching dust shroud everything.

Liu knew little about occupational safety and even if he did, he would still take the risks in pursuit of better payment and thus a better life.

The job cost him too much, damaging his lungs and dragging him to death's door.

Liu was diagnosed with pneumoconiosis in 1998, and in the following years, he was like a prisoner on death row, waiting for the day to come.

Liu did not give up hope without a fight. He and his son once went to a local hospital in nearby Loudi City where a doctor told him his case was "hopeless unless he receives an organ transplant".

Such an operation would cost over 70,000 U.S. dollars, making it an option Liu would never be able to afford. On his way back home, Liu and his son bought a coffin.

Luckily, a phone call from the Hunan Red Cross came that turned out to be the turning point of his life.

"I never expected I would have an organ transplant, even in my wildest dreams," he recalled.

The call was a follow-up interview with the family of the organ donor. Liu's wife had died after an accident in 2015, and he agreed to donate her liver and kidneys.

In the interview, Liu told the interviewer about his own miserable experience. "I was asked to deliver a report about my situation. Finishing the report, I insisted on sending it myself," Liu said. He remembered that it took him almost an hour to climb to the fifth floor where the Red Cross office was.

Several months later, he was admitted into the Second Xiangya Hospital free of charge, waiting for the donated lungs. On Liu's 42nd day in the hospital, the doctor told him to prepare for the operation.

Seeing off the doctor, Liu wrapped his head in his quilt and burst into tears while his son cried out in the bathroom. At the same time, five kilometers south of Liu's hospital, two grieving parents were bidding farewell to their only son.

"I was told my lungs were from a 16-year-old boy about one week after I got out of the ICU. I was shocked. I can totally feel their pain as I am a father and also have a son," Liu said.

The double-blind rule of organ donation prevented Liu from getting in touch with Yesha's parents, but he managed to learn some things about his donor, including his hobby of playing basketball.

That was why Liu jumped at the idea of organizing a basketball team with the recipients of Yesha's organs to honor the Ye family's noble act when the China Organ Donation Administration Center reached him.

Not all the organ recipients were willing to expose their privacy. Out of seven people, five joined in the campaign: Liu; 14-year-old Yan Jing and Huang Shan, each of them taking a cornea; Zhou Bin, recipient of Yesha's liver' and Hu Wei, taking a kidney. They formed a team, appropriately named Yesha.

WCBA ALL-STAR GAME

The Yesha team's performance may be the most special two minutes in the seven-year history of the Chinese women's basketball league All-Star Game.

As the main game went into a break, the five of them, in scarlet jerseys printed with their numbers and organ icons, filed onto the court, while on the big screen, a video telling the story of Yesha and the team was displayed.

"I am Yesha, Yesha's lungs," Liu Fu said in the video.

"I am Yesha, Yesha's eye," Yan Jing said.

"I am Yesha, Yesha's eye," Huang Shan said.

"I am Yesha, Yesha's kidney," Hu Wei said.

"I am Yesha, Yesha's liver," Zhou Bin said.

Their names were called out one by one by ceremony host Liu Xingyu, as the capacity 6,000 crowd welcomed them with a standing ovation, among them former NBA star and current Chinese Basketball Association president Yao Ming.

Yao led the pack in the VIP seats to stand up, clapping his hands, while down on the court, the team's opposing All-Star players wiped tears from their faces.

"I couldn't hold back my tears and when I looked around I found that my teammates were also weeping," said Chinese national team player Shao Ting.

"I was deeply moved by the story, as were my teammates. This boy and his parents were great. They did a wonderful deed," she continued.

"I haven't told my parents about this, but I am seriously considering to become an organ donation volunteer now," she said.

Apart from Zhou Bin, no one in Team Yesha knew how to play basketball. Hu Wei barely even touched the ball during the two minutes.

They ran around on the court and made a number of attempts to shoot, with the help of their amenable opponents who did not attack and instead fed them with baskets. Zhou finally managed to nail a jump shot and a free throw before the whistle, amid deafening cheers from the partisan spectators.

"I heard that Yesha loved playing basketball, and that he had hoped to take part in competitions one day. I felt obliged to realize his dream for him," said Zhou Bin, a 53-year-old policeman from Guangxi.

"My privacy is nothing compared to what Yesha's family have lost," he added.

Yan Jing was the only other Team Yesha member who succeeded in scoring in the game - or more precisely, right after the final whistle.

Encouraged by Shao Ting, she flung the ball toward the basket and missed the hoop, once, twice, three times. But on her fourth attempt, the ball bounced around the inside of the hoop and dropped in. Both teams jumped with joy.

"I was very, very happy! I did this with his eye," said Yan Jing.

The All-Star Game drew to close on the night of January 27, but it helped focus huge media coverage on Team Yesha and China's organ donation drive, and triggered an explosion of volunteer registrations.

In an interview two days after the game, China Organ Donation Administration Center official Zhang Shanshan told reporters that a total of 900,000 people had registered to donate their organs by the end of January. More than three months later, that number has exceeded 1.22 million.

Yesha's parents did not go to see the game live, instead watching it later online. Papa Ye cried and Mama Ye's insomnia recurred.

"Since Yesha passed away, I have an extremely low threshold for crying, and getting emotional at little things," said Papa Ye.

"But I received great comfort. When I saw them running on the court, it seemed like my son was still with us. Looking at the lives Yesha saved, I am truly happy for them. I believe I did the right thing, from the bottom of my heart," he said.

Losing their son left a permanent hole in their lives, as Yesha's parents now try to fill their time with the busy schedules of promoting organ donation and operating a home bakery.

Mama Ye used to cook for Yesha, and now her son's old bedroom has been turned into the bakery room. She makes Chinese dim sum and various cakes and sells her food online, with her business booming.

Liu Fu also started his new life.

He works part-time in a housekeeping service company and also as a devoted volunteer to promote organ donation.

One day, as he volunteering at the Second Xiangya hospital, he passed a middle-aged couple. At that very moment, there was a strange feeling surging inside him that made his heart racing fast.

"I felt like I had lost the ability to speak and my heart was fluttering for the rest of the day. Later I was told that those two people were Yesha's parents," Liu recalled.

(Yesha, Liu Fu, Yan Jing, Huang Shan, Zhou Bin and Hu Wei are all pseudonyms.)

(Video editor: Gao Shang)